1. Introduction: Why Kubernetes Matters

As organizations scale their software delivery using containers, they quickly encounter a new challenge: managing those containers reliably, securely, and at scale. Running a few containers on a single machine is relatively simple. Running hundreds or thousands of containers across multiple environments, teams, and regions is not.

Kubernetes (often abbreviated as K8s) emerged to solve this problem. Originally developed at Google and later open-sourced, Kubernetes has become the de facto standard for container orchestration. Today, it underpins modern DevOps practices across startups, enterprises, and cloud-native organizations.

2. The Problem Kubernetes Solves

Before Kubernetes, teams manually deployed applications on servers or virtual machines. Scaling required provisioning new machines, configuring them, and deploying applications by hand. This process was slow, error-prone, and difficult to automate.

Containers simplified application packaging, but they introduced a new layer of complexity:

- How do you start and stop containers automatically?

- How do you scale them based on demand?

- What happens when a container crashes?

- How do containers discover and communicate with each other?

- How do you deploy updates without downtime?

Kubernetes addresses these challenges by acting as a control plane for containerized applications. It continuously monitors the desired state of your system and works to ensure the actual state matches it.

3. What Kubernetes Is and Is Not

Kubernetes is a container orchestration platform. It automates the deployment, scaling, networking, and lifecycle management of containerized applications.

Kubernetes is:

- A platform for running containers at scale

- Declarative, which means you describe what you want, Kubernetes figures out how

- Highly extensible and cloud-agnostic

- Designed for resilience and automation

Kubernetes is not:

- A replacement for Docker

- A CI/CD tool

- A monitoring solution

- A magic solution for poor architecture

Understanding these boundaries helps teams adopt Kubernetes realistically.

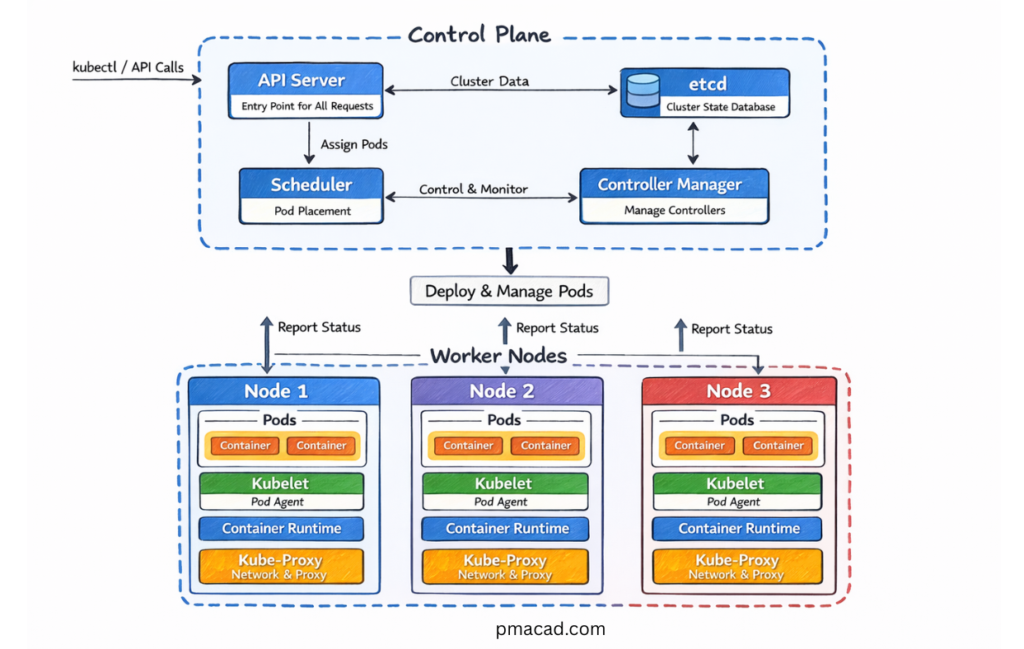

4. Kubernetes : Architecture & Working

At a high level, Kubernetes consists of a cluster made up of:

- A control plane (brains of the system)

- One or more worker nodes (where applications run)

In Kubernetes, a cluster is the complete environment where your containerized applications run. It is a collection of machines—called nodes—that work together under Kubernetes control to deploy, manage, and scale applications. You can think of a cluster as the boundary of control for Kubernetes: everything Kubernetes manages lives inside a cluster.

A Kubernetes cluster has two main parts: the control plane and the worker nodes. The control plane is responsible for managing the cluster. It makes decisions about scheduling, tracks the desired and actual state of applications, and responds to changes such as failures or scaling requests. The worker nodes are the machines where application workloads actually run. Each worker node hosts Pods, which in turn run containers.

The cluster provides the shared infrastructure needed for applications to operate reliably. Networking, storage, security policies, and resource management are all handled at the cluster level. When you deploy an application, Kubernetes decides which node in the cluster should run its Pods and continuously ensures that the application remains healthy according to its defined configuration.

From a practical perspective, a cluster represents both a technical and operational unit. Teams often create separate clusters for different purposes, such as development, testing, and production, or for regulatory and security isolation. Understanding what a cluster is helps clarify where Kubernetes applies control, how resources are shared, and how applications are managed at scale.

Let me break it down and highlight some key points for extra clarity:

3.1 Control Plane Components

The control plane manages the cluster and makes global decisions.

API Server

The API server is the front door to Kubernetes. All commands—whether from users, automation, or internal components—go through it.

etcd

etcd is a distributed key-value store that holds the cluster’s configuration and state.

Scheduler

The scheduler decides where to place new workloads based on resource availability and constraints. The Scheduler assigns Pods to Nodes based on resources and constraints.

Controller Manager

Controllers continuously monitor the cluster and reconcile differences between desired and actual state.

3.2 Worker Node Components

Worker nodes run application workloads.

kubelet

The kubelet communicates with the control plane and ensures containers are running as expected.

Container Runtime

This is the software that actually runs containers (Docker, containerd, etc.).

kube-proxy

Handles networking and traffic routing within the cluster.

5. Core Kubernetes Concepts

5.1 Pods

A Pod is the smallest and most basic unit that Kubernetes works with. Instead of managing individual containers, Kubernetes schedules and manages Pods. A Pod represents a single instance of an application running in the cluster and acts as a wrapper around one or more containers. In most real-world scenarios, a Pod contains just one container, but Kubernetes allows multiple containers to run together inside the same Pod when they need to be tightly coupled.

All containers within a Pod share the same network and storage context. A Pod is assigned a single IP address, and the containers inside it communicate with each other using localhost. Pods can also share volumes, which allows containers to exchange data or persist files during the Pod’s lifetime. This shared environment is what makes Pods a logical execution unit rather than just a grouping of containers.

Pods exist to make containerized applications easier to manage at scale. By grouping containers into a Pod, Kubernetes can schedule them together on the same node, restart them together, and scale them as a single unit. This abstraction allows Kubernetes to treat an application instance consistently, regardless of what is happening inside the container runtime.

Pods are ephemeral by design. They can be created, destroyed, and recreated at any time, especially during scaling operations, updates, or node failures. When a Pod fails, Kubernetes does not repair it; instead, a new Pod is created to replace it. Because of this, Pods are usually managed by higher-level controllers such as Deployments, StatefulSets, or Jobs, rather than being created directly.

In practical Kubernetes usage, Pods form the foundation on which everything else is built. Services route traffic to Pods, Deployments manage their lifecycle, and scaling decisions ultimately result in Pods being created or removed. Understanding Pods is essential for grasping how Kubernetes applications are deployed, scaled, and operated in real production environments.

5.2 Deployments

A Deployment is a higher-level Kubernetes object that manages Pods and ensures an application is always running in its desired state. Instead of creating and maintaining Pods manually, teams define a Deployment and let Kubernetes handle the operational complexity. A Deployment continuously monitors the cluster and makes sure the specified number of Pod replicas are running at all times.

One of the primary responsibilities of a Deployment is replica management. If a Pod crashes, is deleted, or a node fails, the Deployment automatically creates new Pods to replace the lost ones. This self-healing behavior is what makes Kubernetes reliable in production environments. Scaling an application is equally straightforward—by changing the replica count, Kubernetes adds or removes Pods without disrupting the service.

Deployments also provide built-in support for rolling updates. When a new version of an application is released, the Deployment gradually replaces old Pods with new ones based on a defined strategy. This controlled rollout minimizes downtime and reduces risk, allowing teams to deploy changes safely. If issues are detected during an update, Deployments support rollbacks, enabling teams to quickly revert to a previous stable version.

From a delivery and operations perspective, Deployments simplify day-to-day application management. They allow teams to deploy new versions with confidence, scale applications in response to demand, and recover automatically from failures—all without manual intervention. Because of this, Deployments are the most commonly used controller for running stateless applications in Kubernetes and form a cornerstone of modern DevOps practices.

Deployments allow teams to:

- Deploy new versions safely

- Scale applications easily

- Recover automatically from failures

5.3 ReplicaSets

A ReplicaSet is a Kubernetes object responsible for ensuring that a specified number of identical Pod replicas are running at any given time. Its core purpose is simple but critical: maintain availability. If a Pod crashes, is deleted, or becomes unhealthy, the ReplicaSet automatically creates a new Pod to replace it, ensuring the desired state is preserved.

ReplicaSets work by continuously comparing the desired number of Pods with the actual number running in the cluster. When there is a mismatch, Kubernetes takes corrective action by creating or removing Pods. This makes ReplicaSets a key building block for scalability and fault tolerance in Kubernetes applications.

In practice, teams rarely interact with ReplicaSets directly. Instead, Deployments manage ReplicaSets behind the scenes. Each time a Deployment is created or updated, it creates a new ReplicaSet to represent the desired version of the application. During rolling updates, the Deployment gradually scales down the old ReplicaSet while scaling up a new one, allowing smooth transitions between versions.

Understanding ReplicaSets helps clarify how Kubernetes achieves reliability and controlled updates. While Deployments provide the user-friendly interface for application management, ReplicaSets do the underlying work of keeping Pods running consistently. Together, they form the foundation for scalable, self-healing workloads in Kubernetes.

5.4 Services

Pods in Kubernetes are ephemeral by nature. They can be created, destroyed, or replaced at any time due to scaling events, updates, or failures. When this happens, their IP addresses also change. Because of this, directly connecting to Pods is unreliable and impractical for real-world applications. Kubernetes solves this problem using Services.

A Service is a stable, long-lived abstraction that provides consistent network access to a group of Pods. Instead of talking to individual Pods, applications and users communicate with a Service. The Service automatically routes traffic to healthy Pods behind it, even as Pods are recreated or scaled. This decouples application connectivity from the underlying Pod lifecycle.

Services work by using labels and selectors to identify which Pods they should route traffic to. As long as Pods match the Service’s selector, they are included in traffic routing. Kubernetes handles load balancing and service discovery, allowing applications to remain available without hardcoding Pod IP addresses.

Kubernetes supports several Service types, each designed for different access needs.

- ClusterIP is the default Service type and exposes Pods only within the Kubernetes cluster. It is used when an application component, such as a backend or database service, should be accessible only to other services running inside Kubernetes and not to external users.

- NodePort exposes a Service on a fixed port on every cluster node, allowing external access using the node’s IP address and that port. It is simple to set up and useful for development, testing, or quick demos, but it is usually avoided in production due to security and scalability limitations.

- LoadBalancer exposes a Service externally using a cloud provider–managed load balancer, providing a single, stable IP address or DNS name. It is the preferred option for production workloads that need to be accessed from the internet, as it offers better reliability, scalability, and integration with cloud networking.

From an architectural and delivery perspective, Services are essential for building reliable Kubernetes applications. They provide stability, enable scaling, and ensure seamless communication between components, even as the underlying Pods constantly change.

5.5 Namespaces

Namespaces provide logical isolation within a cluster. They are commonly used to separate environments, teams, or applications.

A Namespace is a logical partition within a Kubernetes cluster that helps organize and isolate resources. Instead of running everything in a single shared space, namespaces allow teams to group related objects—such as Pods, Deployments, Services, and ConfigMaps—under a common boundary. This makes large clusters easier to manage, understand, and govern.

Namespaces are most commonly used to separate environments, teams, or applications. For example, a single cluster might have separate namespaces for development, testing, and production, or different namespaces for individual teams or business units. This separation reduces accidental interference and improves operational clarity without requiring multiple clusters.

Namespaces also play an important role in access control and governance. Using Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), permissions can be scoped to a specific namespace, ensuring teams only have access to the resources they are responsible for. Resource quotas and limits can also be applied at the namespace level, helping control resource consumption and prevent one workload from impacting others.

While namespaces provide logical isolation, they do not offer full security isolation like separate clusters or virtual machines. However, they strike a practical balance between flexibility and control. In real-world Kubernetes environments, namespaces are essential for structuring clusters, enabling multi-team collaboration, and enforcing operational boundaries at scale.

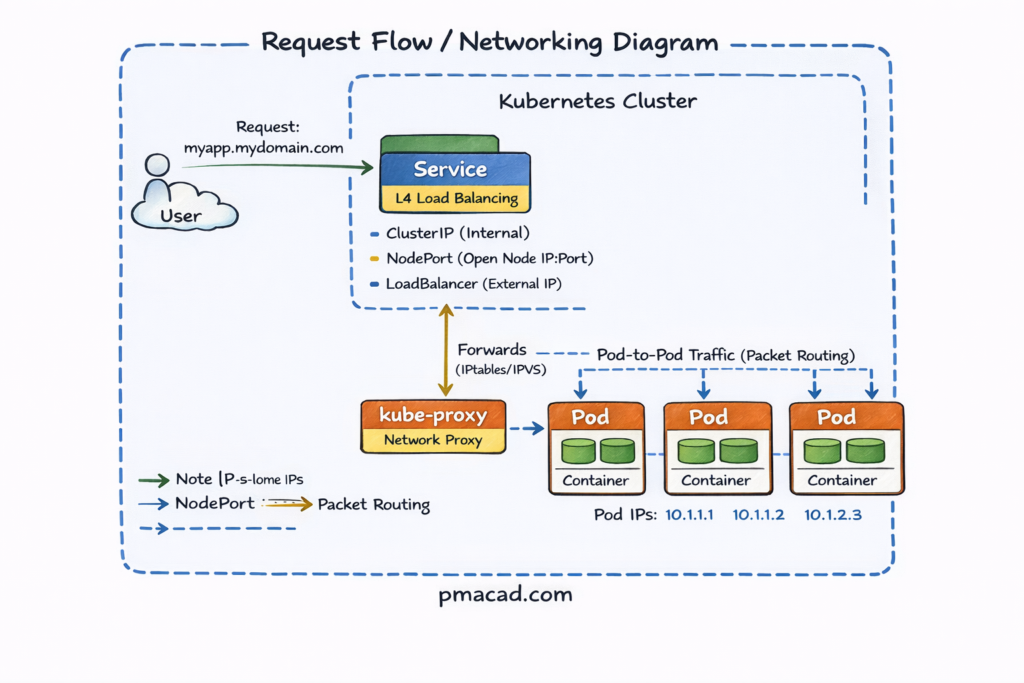

6. Kubernetes Networking

Kubernetes networking is a foundational concept that enables communication between users, services, and applications running inside a cluster. Unlike traditional systems, Kubernetes assumes a flat, routable network where every Pod can communicate with every other Pod without Network Address Translation (NAT). This design simplifies application development but requires a well-defined networking model to manage traffic efficiently and securely at scale.

At a high level, Kubernetes networking governs how external requests enter the cluster, how traffic is routed internally, and how responses are returned to clients. Requests typically flow from users through ingress points such as load balancers and Ingress controllers, then through Services that provide stable virtual IPs and load balancing, before reaching the target Pods. Components like kube-proxy and the Container Network Interface (CNI) plugin work together to route traffic and enforce networking rules.

From an architectural perspective, Kubernetes networking spans multiple layers—external access, service discovery, internal routing, and pod-level communication. This layered approach allows Kubernetes to support scalable, resilient applications while abstracting the complexity of underlying infrastructure. Understanding this request flow and networking architecture is essential for designing performant, secure, and highly available Kubernetes applications.

Kubernetes networking follows a few key principles:

- Every Pod gets its own IP

- Pods can communicate without NAT

- Services abstract Pod IP changes

Kubernetes Request Flow / Networking

- User Request

- A user sends an HTTP/HTTPS request (e.g.,

myapp.mydomain.com) from the internet.

- A user sends an HTTP/HTTPS request (e.g.,

- Ingress

- The request first reaches the Ingress, which acts as an L7 (HTTP/HTTPS) router.

- Ingress applies rules based on hostnames and paths and decides which Service should receive the traffic.

- Service

- The request is forwarded to a Service, which provides a stable virtual IP for a group of Pods.

- Service performs L4 load balancing and can be exposed as:

- ClusterIP (internal only)

- NodePort (open port on every node)

- LoadBalancer (cloud-provider external IP)

- kube-proxy

- kube-proxy runs on every node and programs iptables/IPVS rules.

- It forwards traffic from the Service IP to one of the healthy Pod IPs.

- Pods

- Traffic finally reaches a Pod using its internal Pod IP.

- The container inside the Pod handles the request.

- Response Path

- The response travels back along the same path to the user.

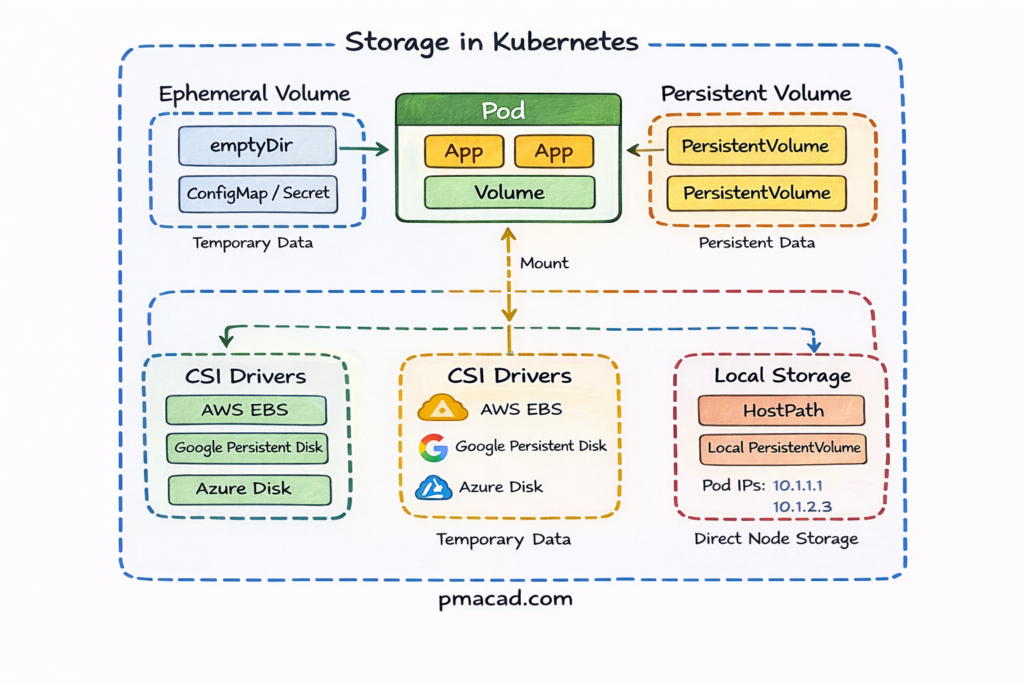

7. Storage in Kubernetes

Applications often need persistent data. Kubernetes supports this through:

Volumes

Volumes in Kubernetes provide a way for Pods to store and share data during their lifecycle. Unlike container filesystems, which are ephemeral, volumes persist as long as the Pod exists and can be shared between containers within the same Pod. Volumes are tightly coupled to the Pod’s lifecycle—when the Pod is deleted, the volume is typically removed as well. Kubernetes supports many volume types, including emptyDir, configMap, and secret volumes. Volumes are commonly used for temporary storage, configuration data, and inter-container communication, but they are not suitable for long-term persistence.

Persistent Volumes (PV)

Persistent Volumes represent storage resources provisioned independently of Pods. They abstract the underlying storage infrastructure, such as cloud disks, NFS shares, or block storage, into a cluster-wide resource managed by Kubernetes. PVs have a defined capacity, access mode, and reclaim policy, allowing administrators to control how storage is used and recycled. Because PVs exist independently of Pods, they can survive Pod restarts and rescheduling. This separation enables reliable data persistence and makes PVs essential for running stateful applications in Kubernetes environments.

Persistent Volume Claims (PVC)

Persistent Volume Claims are requests for storage made by applications. Instead of directly interacting with storage infrastructure, Pods reference PVCs to request a specific amount of storage with certain access requirements. Kubernetes automatically binds a PVC to a matching Persistent Volume or dynamically provisions one using a StorageClass. This decouples application configuration from storage implementation, allowing developers to focus on application needs while operators manage storage details. PVCs make storage self-service, portable, and consistent across different environments and cloud providers.

This abstraction allows Kubernetes to work across cloud and on-prem environments.

8. Configuration and Secrets Management

Hardcoding configuration into containers is a bad practice. Kubernetes provides:

ConfigMaps

ConfigMaps are used to store non-sensitive configuration data separately from application code. They allow you to externalize configuration such as application settings, feature flags, environment-specific values, and command-line arguments. By decoupling configuration from container images, ConfigMaps make applications more portable and easier to manage across different environments like development, staging, and production. ConfigMaps can be injected into Pods as environment variables, command-line arguments, or mounted as configuration files. Updating a ConfigMap enables configuration changes without rebuilding container images, improving flexibility and supporting modern configuration management practices in Kubernetes.

Secrets

Secrets are designed to store and manage sensitive information such as passwords, API keys, tokens, and certificates. They provide a safer alternative to hardcoding credentials in application code or container images. Secrets can be injected into Pods as environment variables or mounted as files, allowing applications to access sensitive data securely at runtime. Kubernetes stores Secrets in etcd and can encrypt them at rest, while access is controlled through RBAC policies. Proper use of Secrets reduces the risk of credential exposure and helps enforce security best practices in Kubernetes environments.

9. Scaling and Self-Healing

One of Kubernetes’ biggest strengths is automation.

Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA)

The Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA) automatically adjusts the number of running Pods for an application based on observed resource usage or custom metrics. Most commonly, HPA scales Pods up or down based on CPU or memory utilization, but it can also use application-level or external metrics. By continuously monitoring these metrics, Kubernetes ensures applications have enough capacity to handle traffic spikes while avoiding over-provisioning during low demand. HPA enables efficient resource usage, improves application performance, and supports elastic, cost-effective scaling without manual intervention.

Self-Healing

Self-healing is a core Kubernetes capability that ensures applications remain available despite failures. If a Pod crashes or becomes unhealthy, Kubernetes automatically restarts it based on defined health checks. When an entire node fails, Kubernetes reschedules affected Pods onto healthy nodes in the cluster. Controllers continuously monitor the desired state and take corrective actions when the actual state diverges. This automated recovery reduces downtime, minimizes manual operations, and allows applications to remain resilient in dynamic and failure-prone environments.

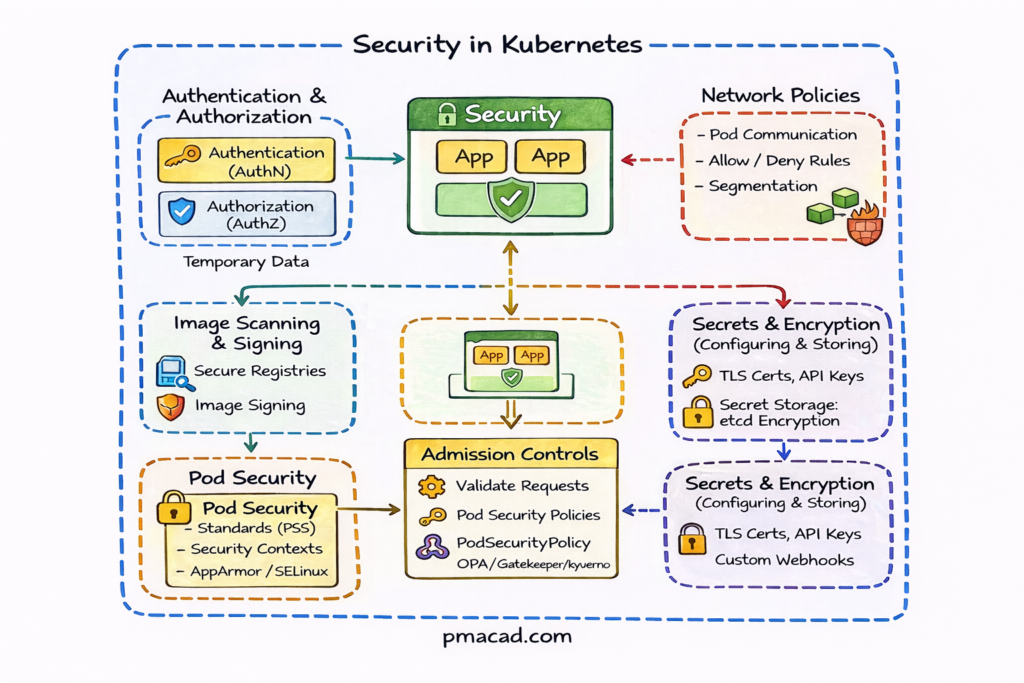

10. Security in Kubernetes

Security in Kubernetes is built on a layered, defense-in-depth approach that protects clusters, workloads, and data at every stage. It starts with strong authentication and authorization for API access, continues with policy enforcement and secure workload configuration, and extends to network isolation and encrypted secrets management. By combining identity controls, admission policies, runtime protections, network rules, and secure storage, Kubernetes enables teams to run containerized applications safely while minimizing attack surfaces and limiting the impact of potential breaches.

This diagram shows how Kubernetes security is applied in multiple layers, protecting workloads from the moment a request is made until the application runs inside a Pod.

Authentication & Authorization (AuthN / AuthZ)

- Authentication verifies who is making the request (users, services, tokens, certificates).

- Authorization determines what actions are allowed using RBAC.

- Every request to the Kubernetes API Server passes through this layer first.

Admission Controls

- Admission controllers validate or modify requests before objects are created.

- Used to enforce security rules such as:

- Allowed images

- Required labels

- Pod Security standards

- Tools like OPA Gatekeeper or Kyverno extend this layer.

Pod Security

Controls what a Pod is allowed to do at runtime.

- Includes:

- Pod Security Standards (PSS): Privileged, Baseline, Restricted

- Security contexts (run as non-root, read-only filesystem)

- AppArmor / SELinux for kernel-level isolation

Image Scanning & Signing

- Ensures only trusted container images run in the cluster.

- Images are:

- Scanned for vulnerabilities

- Signed and verified before deployment

- Prevents supply-chain attacks.

Network Policies

- Control Pod-to-Pod and Pod-to-Service communication.

- Define:

- Which Pods can talk to each other

- Allowed ingress and egress traffic

- Enables zero-trust networking inside the cluster.

Secrets & Encryption

- Sensitive data (API keys, passwords, certificates) are stored as Kubernetes Secrets.

- Secrets are:

- Encrypted at rest in etcd

- Mounted into Pods or injected as environment variables

- TLS certificates secure communication between components.

10. Stateful Workloads and Storage

Stateful vs Stateless Workloads

Stateless Workloads

- Stateless workloads do not store data locally between requests. Each request is independent, and any instance of the application can handle it. If a Pod is restarted or replaced, no data is lost. Stateless applications are easy to scale horizontally and recover quickly from failures.

- Examples: web servers, APIs, frontend applications, batch processors.

Stateful Workloads

- Stateful workloads maintain persistent data or state across requests and restarts. They require stable storage, consistent identity, and controlled startup and shutdown. If not handled correctly, data loss or inconsistency can occur.

- Examples: databases, message brokers, caches, search engines.

While Kubernetes is well known for running stateless applications, most real-world systems depend on persistent state. Databases, distributed caches, message brokers, and legacy enterprise applications all require data to survive Pod restarts, rescheduling, and scaling events. Kubernetes addresses this through dedicated abstractions for stateful workloads and storage management. By separating compute from storage and introducing declarative storage APIs, Kubernetes enables applications to scale reliably without sacrificing data integrity. This makes it possible to run production-grade, stateful systems in dynamic, cloud-native environments while maintaining consistency, durability, and operational simplicity.

StatefulSets

StatefulSets are a Kubernetes workload controller designed specifically for stateful applications that need stable identities and persistent storage. Unlike Deployments, StatefulSets ensure that each Pod has a unique, predictable name, a stable network identity, and a dedicated persistent volume that remains attached even if the Pod is restarted or rescheduled.

StatefulSets also provide ordered Pod creation, scaling, and termination, which is critical for databases and clustered systems that rely on leader–follower or quorum-based architectures. Common use cases include relational databases, NoSQL stores, message queues, and distributed storage systems where data consistency and identity are essential.

Storage Classes and Dynamic Provisioning

StorageClasses define how storage is dynamically provisioned in Kubernetes. They act as an abstraction layer between applications and the underlying storage systems, such as cloud block storage, network file systems, or on-prem storage solutions. Instead of manually creating volumes, applications request storage through PersistentVolumeClaims, and Kubernetes uses the associated StorageClass to automatically create the required storage.

StorageClasses allow administrators to specify policies such as performance type, replication, encryption, and reclaim behavior. This enables self-service storage, consistent configurations across environments, and efficient management of storage at scale for stateful workloads.

With dynamic provisioning, Kubernetes automatically creates storage volumes when applications request them, eliminating manual coordination between infrastructure and application teams. This improves agility, enables self-service storage, and ensures consistent storage policies across environments. StorageClasses also allow tuning of performance, replication, and cost characteristics, making them a key component for running scalable, stateful applications efficiently in Kubernetes.

12. Conclusion: Kubernetes as a Long-Term Capability

Kubernetes is not just a technology—it is an operating model for running software at scale. While it introduces complexity, it also enables levels of automation, resilience, and consistency that were previously difficult to achieve.

For IT and DevOps professionals, Kubernetes is a career-defining skill. For project and delivery leaders, it is a strategic capability that shapes how modern software organizations operate.

The real value of Kubernetes emerges when it is combined with strong DevOps practices, thoughtful governance, and continuous learning. Teams that invest in understanding Kubernetes holistically—across architecture, operations, security, and delivery—are better equipped to build resilient platforms and sustain long-term success.

Rather than treating Kubernetes as a one-time adoption, successful organizations view it as a continuously evolving capability. With the right mindset and leadership, Kubernetes becomes a powerful foundation for modern IT delivery rather than a source of unmanaged complexity.